On Paper

A Series of (un)Censored Experience

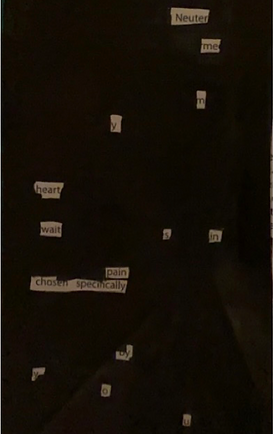

01

I Have Uncensored Your Touch

Neuter me

My heart waits in pain

Chosen specifically

By you

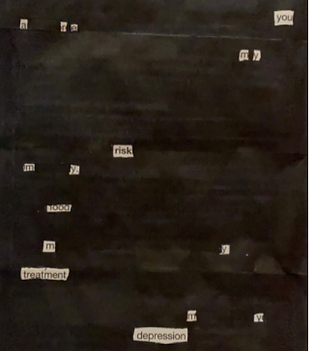

02

I Have Uncensored Your Abuse

You are my risk

My food

My treatment

My depression

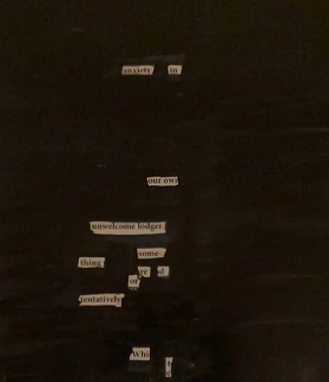

03

I Have Uncensored My Abortion

Anxiety in our own

Unwelcome Lodger.

Something red

or

Tentatively white

04

Black-out Poetry: In Consensus or Contradiction to Human Rights?

In an article exploring the different formats of ‘found poetry,’ Emily Ramser highlights the key difference between erasure poetry and blackout poetry; “Where erasure relies on subtraction, blackout poetry depends on addition.” The emphasis on this addition is vital in exploring the ways in which blackout poetry speaks to contemporary experience as it makes clear that the words ‘blacked-out’ are not removed, rather out of sight. This plays into important debate surrounding issues of censorship and its evolution in contemporary literature.

Censorship has played a massive role in modern to contemporary literature following Oscar Wilde’s trial of 1895, setting off a mass of trials debating the censorship of D.H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow 1915, James Joyce’s Ulysses 1922, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness 1928 and, of course, Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1928 and again in 1960. The 1950s, 1960s and 1970’s saw a dramatic shift away from censorship in Western literature, with an increase of freedom of speech enforced by feminist and anti-racist activists, as well as the sheer impact of the world wide web and the ability to publish, independently, as a result. That being said, the issue of censorship remains a prominent and crucial debate. As presented by Nicole Moore, the list is contemporary writers who have been either banned, imprisoned or murdered remains exhaustive, with her mentioning:

Nadine Gordimer, Wole Soyinka, Ariel Dorfman, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Dario Fo, Juan Goytisolo, Judy Blume, Nawal Saadawi, Salman Rushdie, Yaşar Kemal, Anna Politkovskaya,

to name a few. In a society in which freedom of speech and self-expression is regarded highly, and to some extent, vital, I would argue that the rising form of blackout poetry acts as a political polemic against censorship. While blackout poetry mimics the form of censorship, its purpose is purely to choreograph a new poem through a body of work that already exists; perhaps a piece that bears resemblance to its predecessor and perhaps one with no relation. Confirming this political use of blackout poetry, the Hamilton Public Library held an event for ‘freedom to read week’ (in Canada) inviting people to create blackout poetry out of books that had been previously protested, with Millward arguing that this form of blackout poetry is “a form of visual and intellectual art that uses contentious books that have been banned in the past to create a piece that celebrates free expression. Inspired by this, I attempted to experiment with blackout poetry that rather put a spotlight on topics often censored or withheld- including sexuality, abuse and abortion.

This attack on censorship seems extremely pertinent to Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, a text which, according to the American Library Association, was the second most challenged book of 2013 and the fourth most challenged book of 2014 with people arguing against its “sexually explicit material,” and “lots of graphic descriptions and lots of disturbing language.” Like the aforementioned texts, Morrison’s first book was banned successfully in several states for being “lewd,” “sexually explicit” and “a false narrative about black life.” Just as blackout poetry physically mutes certain words, Morrison’s book was muted and ultimately blacked out from society for several years in a clear disregard of freedom of speech.

That being said, others have implemented blackout poetry as a way to erase, or arguably censor, misogynistic language in literature that perpetuates the objectification of women in western society. In her piece Fifty Shades of Beige, Kate Arnold implemented the form of found, or blackout poetry, in a way which did not redact female pleasure in E. L. James’s writing, but rather to remove “the male gaze and control of these acts.”

This malleability of language that blackout poetry boasts enables the complete manipulation of meaning which, in this instance, has been used to shift the narrative from “an unhealthy relationship that is presented as something that the reader should want,” to a celebration of female sexuality and the “body that women are forever being told to cover up”. While Arnold explains this experience as a “cathartic exercise,” the notion of censoring bigoted language opens up an interesting debate in contemporary literature: does freedom of speech have limitations? The index of censorship asserts that “freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. It reinforces all other human rights, allowing society to develop and progress. The ability to express our opinion and speak freely is essential to bring about change in society.” However, the unfortunate misuse of this freedom of speech and expression, such as the sheer objectification in James’s Fifty Shades of Grey, creates an unfortunate and difficult to navigate paradox in terms of what should, or should not be censored. While Arnold’s piece implements an intentional censorship that is described to be digressive towards society, it mutes an outdated and damaging narrative that produces its own form of oppression through female objectification and fetishization. Margarita Salas argues that, while freedom of speech is important regarding human rights, it cannot be hierarchized and thus “does not trump the right to live a life free of violence. It also means that there are limits to freedom of expression that are legitimate in order to strike a balance with other human rights.” In addition to this, The Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers Recommendation identifies certain form of expression that are excluded from the parameters of freedom of speech, including: “all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms on hatred based on intolerance, including: intolerance expressed by aggressive nationalism and ethnocentrism, discrimination and hostility against minorities, migrants and people of immigrant origin.” However, this definition does not appear to factor in harmful behaviour towards women, causing contention as to whether Arnold’s blackout poetry is an unjust censorship of free speech or a removal of hate speech. In relation to the current definition of hate speech, feminist Donna Lilian argues that “sexist speech can be framed as hate speech, as it functions to denigrate women as a group, in service, ultimately, of patriarchal subjugation,” going on to explain that while, in representing more than half of the world’s population, women may not be viewed as a minority, society is “organised in such a way that ‘women’ as a class are subordinate to ‘men’ as a class, and it systemically discriminates against women.” This thus suggests the influx of blackout poetry that aims to reframe misogynistic works does not impede the increasing acceptance of freedom of speech.

In blacking out most words from leaflets, I aimed to produce poems that highlighted topics that have often been censored, offering a sheer contrast in which themes of female sexuality, abusive relationships and abortion have been meanwhile other, ‘non-contentious’ ideas have been blacked out. I believe that this experiment with censorship holds an incredible relevance to the ongoing debate of censorship in contemporary literature.